Homer, Alaska

Empowering global communities via the advancement of music policy

1. Introduction

The Center for Music Ecosystems is privileged to lead The Music Policy Resilience Network into its third year, as the program continues to develop and demonstrate its relevance to participating towns, cities, and communities, as well as providing broader benefits to those able to gain from the findings and recommendations presented in this report and the accompanying reports for all participating cities.

The Music Policy Resilience Network emphasizes the role and impact of music ecosystem policy, focusing on how it can be effectively utilized in small, mid-sized, and geographically isolated communities, as well as among those who consider themselves geographical ‘outliers,’ increasing their resilience and resistance to internal and external shocks and disturbances, and enabling them to develop not just in the field of music policy, but across various related policy areas, as befitting need. The work examines how resilience is currently embedded in the music ecosystems of the participating towns and cities, identifies areas requiring further development, demonstrates international best practice case studies, and concludes with a series of actionable recommendations, tailored to each location.

The Music Policy Resilience Network merges both research and practice via the following activities:

Monthly 1.5 hour online masterclasses and workshops focussing on topics requested by members, including ‘Empowering the Artist in the Community’; ‘Music and Tourism’; ‘An Introduction to Music Policy’; ‘The Power of Networks’; and more

1:1 research with cities and stakeholders with an assigned expert consultant, achieved through a combination of literature review, data analysis, stakeholder analysis (interviews, focus groups, written exchanges, surveys, mapping exercises, and more) culminating in a written and freely available report with recommendations

Access to the Music Policy Resilience Network online platform, and direct links with all network members

Opportunities for peer review of ongoing music policy and related projects by other members of the network

Measuring research impact and prospective next steps in each of the communities

Lifetime membership of the network (including access to the online platform and monthly masterclasses).

Join the Network

The Music Policy Resilience Network has evolved into a rolling programme, with towns, cities and communities able to join at any point throughout the year. Contact us to express your interest: info@centerformusicecosystems.com

2. Context

Homer is a 6,000-inhabitant city in the Kenai Peninsula Borough, in Southcentral Alaska – the 3rd least populous state in the U.S., but the largest by land area, spanning 1,477,953.3 km2.

Long known as the “Halibut Fishing Capital of the World” and often dubbed “the end of the road” or the “cosmic hamlet by the sea”, Homer is strongly characterised by its coastal nature, its seasonal flow in visitors, and its spectacular natural scenery – overlooking Kachemak Bay and the Kenai Mountains. Its coastal nature also moderates the climate – subarctic mediterranean –, giving Homer more moderate temperatures as compared to interior Alaska. In terms of transportation and connectedness, Homer, unlike some Alaska towns, is connected to the highway system, the Alaska Marine Highway (the Alaskan ferry system) and it also has an airport.

Homer’s remoteness does not define its vibrancy. While it remains a small town for Alaskan standards too (the most populous cities in Alaska are Anchorage with 286,075, Fairbanks at 31,856, Juneau with 31,555, Badger at 19,033, and Knik-Fairview with 18,921), Homer is well-known for its art scene, particularly the visual arts one.

Known nationally as one of America’s best small art towns, it boasts a thriving arts community encompassing galleries, theaters, live music venues, outdoor sculptures and art exhibitions presenting international and traditional and contemporary Alaska Native works.

Tourism also makes it a vibrant cultural hub, especially during the high season, with several venues opening solely during the summer. For the past 7 years, Homer is also the host of the Alaska World Arts Festival, which takes place every September and features a wide array of artistic expressions including music, dance, theatre and visual arts.

Homer’s music ecosystem is vibrant but small. The scene remains highly seasonal, following the general trend of the town. While live performances play a central role —from local bands to the Kenai Peninsula Orchestra, the scattered nature of the town in terms of urban planning,

the remoteness of it, and the tourism flows define much of the programming. The prominence of the art scene contrasts with the more organic music one, and opens questions of how different creative scenes could better support each other, sharing resources, spaces and protagonism.

3. Deliverables

PHASE 1

Stakeholder engagement

Two roundtables with music professionals, consumers, media and policy professionals, led in person in Homer by Scott Bartlett and Yngvil Vatn Guttu.

PHASE 2

Three best practice international case studies

Three best practice international case studies on the topics of innovative local government support and advocacy for music (1), tourism and night time economy (2); and synergies between cultural and climate resilience policies (3).

4. Methodology

This work has been carried out through a combination of desk research and qualitative interviews, focusing especially in an active involvement of the city contact in the whole process, to maximize the impact and value of the work while it was being produced. The result aims to be a synthesis of this process of work, containing the key findings and possible directions for action.

This work was produced in close collaboration with Scott Bartlett and Yngvil Vatn Guttu, whose availability and willingness to carry out two round tables in person in Homer incredibly enriched the content of this work.

PHASE 1

Stakeholder Engagement

Context and Introduction

The first phase of this MPRN research in Homer consisted of two roundtables with music professionals, consumers, media and policy professionals in Homer. The two sessions took place in spring 2025, engaged a total of 15 participants of diverse professional and personal profiles, and had a strong focus on collective mapping exercises.

The roundtables had three primary goals:

Capturing and mapping the diverse experiences and personal relation of Homerites with the music ecosystem and specific music places in the city.

Through a OCWC (Opportunities / Challenges / Workarounds / Community) exercise done in groups, unpacking the local conditions for music making and experiencing.

Cross-checking with participants their perceptions of tourism, the seasonality of the music scene in Homer, and identify other specific priorities of the ecosystem.

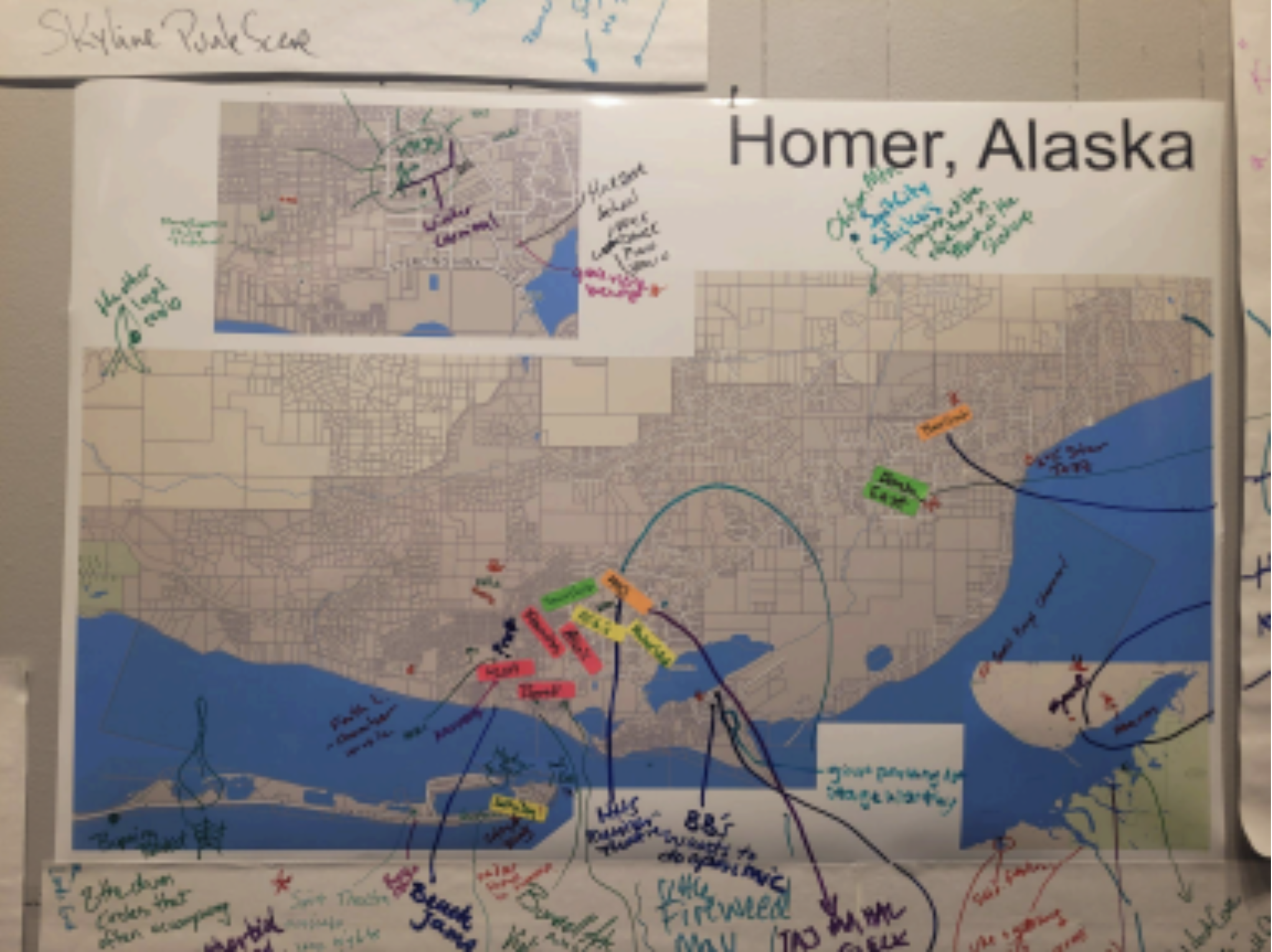

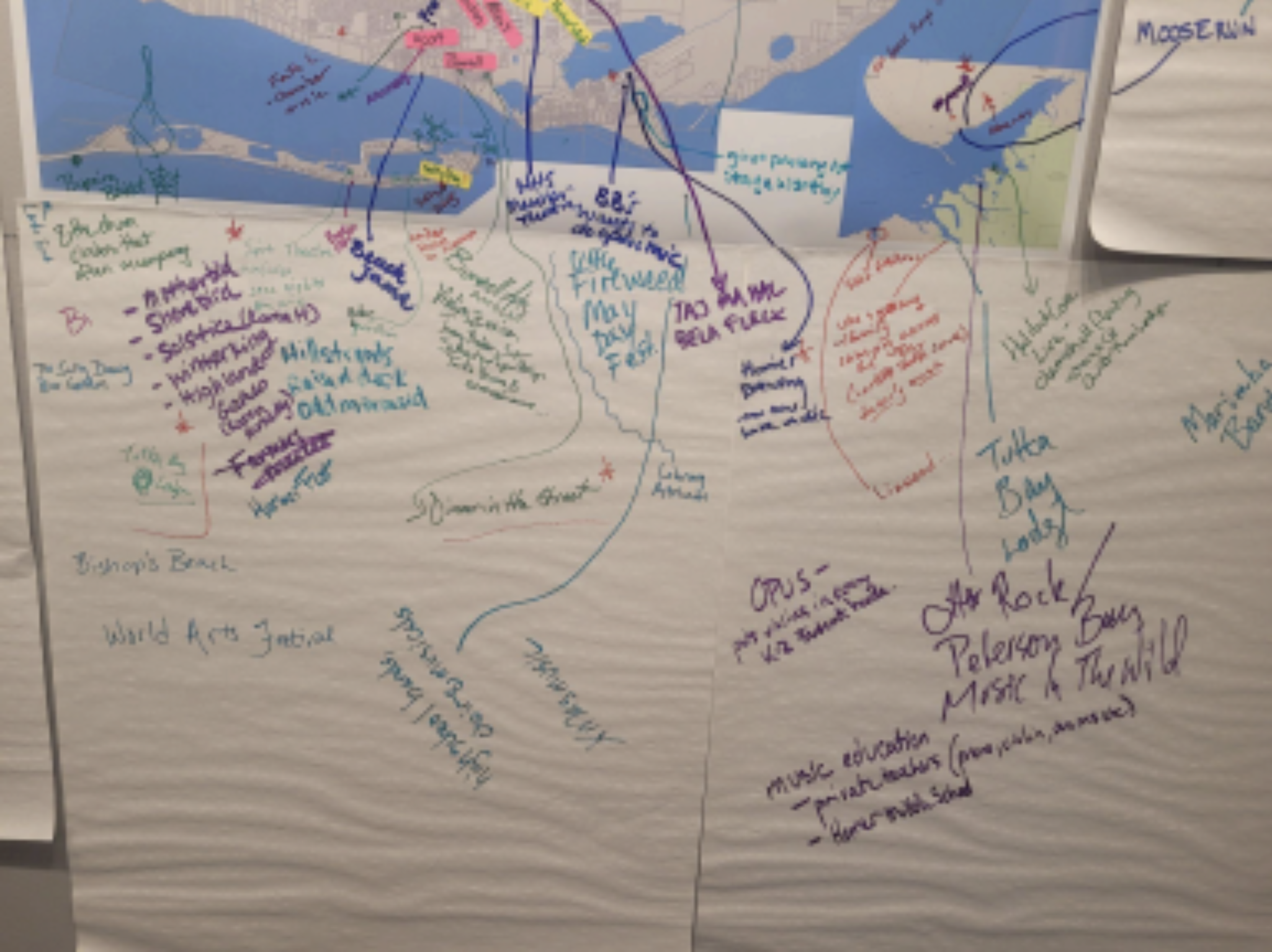

Results of the collective mapping exercise after the first roundtable held in May 2025.

Scott Bartlett and Yngvil Vatn Guttu expressed interest in potentially expanding the mapping activity beyond the scope of the work part of MPRN, and have already digitalised the results of the exercise.

The format of focus groups or roundtables, as opposed to in-depth interviews with individual people, can result in a larger picture of challenges and strategies, but less depth in the way to address those. In order to continue their unpacking, more work would need to be done, tackling the assumptions and underlying elements in all these. The following is a comprehensive summary of the most pressing topics that came to the forefront during the roundtables led in Homer by CME partners Scott Bartlett and Yngvil Vatn Guttu.

Close-ups of the collective mapping exercise after the second roundtable, held in June 2025.

Key Challenges

1. Infrastructure and space

Participants highlighted that the existing spaces (hybrid cultural spaces, venues and institutions) are not used to the fullest of their potential. They also pointed out that there are several venues who used to program music and do not do so any more, arguing that it interferes with the business.

Other underlying challenges related to infrastructure and space are:

Seasonality both in the availability of offer and of audiences

Spaces for production and rehearsal are also greatly missed and are just as important as spaces for performance.

Need for all ages venues as well as medium-sized venues.

2. Professionalisation options and better financial conditions for performers

Several participants mentioned the need for a minimum wage for performers, while they also highlight the precarious working conditions of musicians, who often need to juggle between several jobs to be able to make a living in music.

KEY QUOTE FROM PARTICIPANT

“It was really difficult to put a value on the artists coming in when we were doing music four nights a week. Bars talked about setting up a scale to pay a fair wage, but not everyone wanted to do that. Performers have shopped themselves around to see who will pay them the most. I don’t know what we’re missing to promote this arts identity to the same scale as the Halibut Capital.”

3. Music education

While music is present in public schools, there is a need for more music teachers. The combination of both formal and informal education environments is important and highlighted.

KEY QUOTE FROM PARTICIPANT

“Public schools do a fabulous job in music education given their limited funds; but support outside the school system is needed for both public school-educated and home-schooled kids.”

4. Tourism

While some participants feel the increase in visitors is useful, others feel that Homer is at capacity. Many point out that the economic and urban development model is geared towards visitors, not locals; but overall they all agree that there needs to be a fair balance and that the topic is complicated.

KEY QUOTES FROM PARTICIPANTS

“The other piece that’s a problem are the houses that are being built for short term rentals. Those houses are driving the cost up.”

“I feel like Homer is hitting capacity. We almost can’t house the people working in the city, and the town’s services are under pressure.”

“Tourism equates to recreation. Shopping, eating, listening to music, hiking. That’s the life blood of Homer. Without tourism we don’t fund the school, the harbor, etc. Housing is a problem, but I welcome tourism – that’s what pays the bills. You’ve got to do it the correct way.”

5. Diversity on all fronts: gender, programming, and promotion

Many participants highlighted the need for more diversity in the scene. They also highlighted that while Homer does have a varied offer of different music genres, more could be done. The role of the radio as a promotional tool is also mentioned, as well as the fluctuations in audience numbers as well as performance numbers.

KEY QUOTE FROM PARTICIPANT

“There are far more bands here than there were 25 years ago. The one thing I’ve noticed with the larger ensembles is that the participation doesn’t seem to be as large as it was several years ago. Used to be 60-70 players [in KPO] & now there are often 30. A lot of the players who are playing with HYSOC aren’t playing with anyone else.”

Possible futures and strategies

1. More space for the community to get together

Many participants mention that Homer is a fearless scene already, and that this quality should be expanded on. More access to music-making, more exchange and straight-forward actions such as music equipment in community and neighborhood centres are just some ideas to address this.

KEY QUOTE FROM PARTICIPANT

“People here are a lot more fearless about expressing themselves with music. It’s not the same elsewhere. It’s almost as if they’d say: you’ve got an instrument in your hands – it’s time to show people what you can do.”

2. More and better youth engagement

Youth was a key theme throughout the roundtables – both from a point of view of engaging them as audiences (even economically with, for example, volunteer exchanges or student discounts) but also of equipping them with the tools to pursue music, for example through providing youth centres with music production equipment. The need for all of the spaces that engage youth to be truly safe spaces was also mentioned, especially for the at risk youth population, as well as the need for youth to be included into decision-making processes and actively build youth leadership.

3. Breaking silos and working across sectors

Different actors within the same ecosystem, and different art scenes need to work more together. Ideas such as partnerships with other locally-run businesses or housing for performers and artists as examples of potential and unexplored collaborations were also mentioned.

4. More spaces for performance, rehearsal, and innovative use of space

A variety of ideas were mentioned on the topic of space:

More and diverse programming in the hospitality industry, also on a normal basis (outside of special events).

All ages venues that give control to youth.

Use of public space, and exploring pop up venues as short-term ideas.

Using the city’s flexibility for programming, the fact that it’s relatively easy to put up a show with a relatively short notice.

KEY QUOTE FROM ANONYMOUS PARTICIPANT

“There’s an availability of open venues. There are a lot of opportunities to get shows on short notice.”

5. Advocacy and organisation

There is an overarching agreement that there need to be better ways and efforts to successfully outline the value of the music scene in Homer. Ideas like setting up some type of umbrella association; advocating for local regulations such as a busking code, or stimulating diverse funding (sponsorships, private donations and grants) were mentioned over the course of the two roundtables.

Overview of results of the OCWC exercise carried out in the first roundtable (May 2025)

OPPORTUNITIES

Advocacy or establishing Arts as a municipal department

Access to the Mariner Theatre in the summertime

More places to play

City Code to support busking musicians

Other city code support?

Business partnerships

Donors

Musicians’ Guild (rehearsal space, booking recommendations…)

Performance radius clause in contracts

Cascadia Music Network

Local music promoter/connector

Open Mic nights.

CHALLENGES

Music genre scene–some genres are missing or not well received

Cost for audience

Cost of production (esp tech staff)

Few non-bar venues

Few all ages venues

Hard to go out late at night (esp in winter)

Nobody wants to pay!

Shortage of rehearsal space

Bringing acts south of Anchorage, Hope, Soldotna.

WORKAROUNDS

Volunteering for free admission (HCOA, Pier1, AKWAF)

Partnerships, i.e. in-kind housing

Free events

○ Jam session @ HCOA

○ Free community events (Nutcracker Faire music, solstice fair)

Venue discount for student programs through KPBSD

Second career to fund music making

Grants.

COMMUNITY

Musicians volunteer to play for fundraising events

Programs stimulating arts funding

○ MusicAlaska

○ ASCA: How Are You Creative?

PHASE 2

Three best practice international case studies

Context and Introduction

The second part of this work comprises three reference case-studies in three areas of focus for Homer’s music ecosystem, namely: innovative local government support and advocacy for music, tourism and night time economy, and synergies between cultural and climate resilience policies.

CASE STUDY 1

Innovative local government support and advocacy for music

Old harbour of Tórshavn

Tórshavn Kommune (Faroe Islands)

Tórshavn is the capital and the largest city of the North Atlantic archipelago of the Faroe Islands (Føroyar, one of the three constituent countries forming the Kingdom of Denmark), located in the municipality with the same name (Tórshavnar Kommuna). The city sits on the eastern coast of southern Streymoy, the largest island of the archipelago –approximately 373 km2 – and has traditionally been a harbor city (hence its name, havn). Tórshavn Kommuna has a population of 22,500 (the Faroe Islands has a total of 55,000 inhabitants) and is the seat of the municipal government and the Faroese self-rule government (Føroya Landsstýri) which holds executive power in local government affairs.

The Culture Department of the municipality of Tórshavn has been working over the last couple of years on a new cultural policy. The strategy, which is now finalised, is awaiting ratification from the new Council, elected in January of 2025. While some core features of the new policy are shared by the new coalition, it is likely that the Council may want to amend certain features.

The policy draws from the arts community’s needs, something that Sunnuva Bæek, who has spearheaded the process, is well-aware of, as she has herself worked in the cultural sector for many years both as a project manager in the Nordic House in the Faroe Islands and in various other roles and appointments.

The new cultural policy sets the foundations of the support strategy for the arts, which includes the management of the institutions led by the local council (the music school, the evening school, the public library, a handful of venues and the local museum) as well as guidelines for financial support, best practices and other recommendations.

Generally, the different forms of support of Tórshavn Kommune for the arts community can be summarised as follows:

Core funding grants: local direct funding in the form of small grants for local organisations to cover their general running costs. This is given to both professional and community-run organisations.

Project grants: local direct funding for project grants, which can be large, which can be applied for once a year, or smaller ones, that come out on a rolling basis.

Support funding for national initiatives,

○ The travel funding for export, which covers the travel costs of touring internationally, and is a collaboration with the local airline, the state, and a third party.

○ The regional music initiative, inspired in the danish scheme Regionale Spillesteder, which is essentially a collaboration among different municipalities that promoters all over the archipelago can apply for to get financial support to cover a minimum of the costs to put up a show (basically to be able to cover the minimum wages for musicians and not depend on doorsale or drinks for that).

○ Collaboration in the Arts in schools programme, which covers the costs of having artists of different fields perform and give workshops in regular schools.

Ownership and management of the municipality-run venues. In these, the municipality provides access to the venues (sometimes for a small cut of the door sales, but often for free) while the venue (i.e. the city) covers the cost of staff and other running costs too.

Operationalisation of the newly-built music school, which provides affordable music tuition.

Other forms of support, for example through the provision of affordable work spaces for artists as well as arts organisations and societies; or securing a percentage of every budget for new or refurbished buildings to be dedicated to commissioning art for the building.

Sunnuva Bæk, Senior advisor for culture at Tórshavn City Council: “Even if the new policy is based on the needs of the arts community, it is still not comprehensive enough. While the municipality actively chose to employ a person formerly involved in the arts sector, hence with deep knowledge on the field, there is still a need for a complete mapping of the cultural sector in Tórshavn. We have no data on the value of the arts, only on things like the impact of music in education, and that’s very academic. There is no mapping of the needs of the sector and the impact of culture in society; and the arts community, in general, is not persevering enough at communicating their needs directly to the relevant bodies. They would benefit enormously from better organisation and advocacy in order to make these needs more precise and easier to accommodate.”

Key learnings and important points of connection for Homer:

Diverse streams of public funding contribute to create a more robust ecosystem. This can be achieved both from a point of view of different cultural budgets but also harvesting funding for culture from other budget lines (for example, tourism, heritage, etc.). Securing funding from different administrations on different levels can also act as an incentive for others to chip in.

In small or remote municipalities, strong communication with local organisers at all levels is important. While political roles change often, technical roles inside municipalities often stay longer. Fostering relationships with those, and creating spaces for exchange and mutual learning can be a great way to transmit the challenges and needs of the sector.

Increasing the visibility of volunteers in the scene is crucial. Even if frontrunners and champions of the music and creative scene often will continue to be so and nourish the scene despite the lack of government support, it is absolutely necessary that their existence is known by city officials, so it becomes easier to make the case of their value for the city.

Encourage regional collaboration amongst municipalities. If that is not happening organically or spearheaded by governments themselves, civil society organisations and other stakeholders of the ecosystem can start collaborating across regional “borders”, and bring the case for that collaboration to the administrative level.

Repurposing buildings is flashy and looks good but it’s not easy. Governments often like headline-like announcements such as these, but it is important that they understand the costs of it, and most importantly, the needs of the creative community for such a repurposing to take place.

Lobbying is time and energy-consuming and demands specific skills. If the capacity exists for music offices or cultural organisations to consider opening a (part time) job position for lobbying and advocacy, the impact can be huge and can liberate artistic roles from unnecessary administrative burdens that shrink their creative capacity. Alternatively, asking public authorities for funding specifically to cover the costs of that position can be the first step towards aligning all advocacy efforts.

Data is crucial. Mapping the assets, stakeholders, people and needs of the ecosystem is an unavoidable first step in order to successfully outline the value of the music sector to the city.

CASE STUDY 2

Tourism and night time economy

Cities After Dark / URBACT

Cities After Dark (Europe)

Cities After Dark is the first EU-funded international network of European cities for the revitalisation of the night-time economy. Part of the URBACT programme, the network aims to advance the potential of the night-time economy for development, sustainability and social and economic recovery in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Cities After Dark is a multi-year project (January 2023–December 2025) and comprises a total of 11 European cities, led by Braga (Portugal). The network is composed of three capital cities (Paris, Tallinn and Nicosia) with structured nightlife governance systems in the case of Paris and Tallinn, medium-sized cities (Braga, Genoa, Malaga, Piraeus) aiming to improve the quality of nightlife economy as a factor of city attractiveness and safety, and cities (Budva, Varna, Zadar) with a nightlife mainly linked to seasonal tourist flows, but willing to work to create new opportunities all year round.

In each city there is a working group with a diverse membership - municipal departments, civil society, public or private institutions, etc. These are the so-called URBACT Local Groups, which are responsible for advancing the development of research, drafting policies and reviewing proposals based on the cross-cutting themes of the project.

Representatives of all Cities After Dark cities meet periodically to consolidate and carry out the Integrated Action Plans, strategic action plans located in each of the participating cities whose objectives will be implemented and evaluated throughout the duration of the project. Each city defines priority areas of action according to its specific challenges (safety in Genoa, activation of the city centre in Nicosia, improvement of the perception of the night-time economy in Malaga, etc.) and through joint working sessions with the whole network they fine-tune the implementation actions.

While the focus of the work is night time economy and governance, the working groups apply a broader approach, encompassing a social justice lens, support to local grassroots initiatives, exploring synergies with tourism, and diversifying activities through space and time, among others.

Simone d'Antonio, Lead Expert URBACT network Cities After Dark: “Thinking holistically about city planning also means taking into account diverse challenges – climate change, gender balance, integration, social justice… Many cities in the Cities After Dark network started from a purely night policies approach, but the work is increasingly getting closer to what we refer to as time-based urbanism. Take climate change, for example. Beyond using parks as climate shelters, there’s also another trend now, which is reconsidering the opening hours of museums. Marseille, in France, has started thinking about this: if you’re a tourist, and are visiting the city during summer, most of the day it will be 40ºC and you will just not go out; and if the museum you want to visit closes at 6pm, you quite likely will end up not going there. Keeping these museums open until late is something that is part of a wider reflection on how to organise licensing as well, the opening times of bars, clubs, shops or public services. It’s part of something wider, really going into the direction of a 24-hour city, which is the next objective of many places like London.”

Key learnings and important points of connection for Homer:

Innovative city planning is increasingly holistic, which means it takes into account different layers and fields in the challenges it addresses. In the field of night governance, the idea of “the night” as something not that needs to be managed, but an opportunity for social, cultural, and economic growth of the city is a good example.

Mapping existing resources is key. Understanding where and who are the key cultural players in a city, how they relate to each other, and how they could work alongside each other to achieve a common goal is the foundation of any cross-sectoral strategy.

Culture in general, and music programming in particular, can be tools to change urban development trends. Either through fostering alliances with local businesses, communication campaigns, or creating a network approach, if there are shared priorities, overtouristification or real estate speculation, for instance, can be addressed by making more space for locals and collective ownership through cultural programming, among other ideas.

Think of the city’s infrastructure through the 24h lens. Ports, for example, often run 24h a day, they don’t stop at 6pm. Neither do airports, nor railroads. While in some cities these services are strictly a daytime economy – like in Homer – it remains a useful exercise to think of large-scale infrastructures as actors that impact the flows of the city all day and all night long, in order to unlock management opportunities – what does the overall mobility strategy of the city look like if we think of the connectedness of the port? How can the cultural and music scene benefit from those needs of connectedness?

Public spaces need to be better used. From parks at night as climate shelters, to side streets as improvised stages, to gathering spaces. A strong learning that emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic is that public spaces are public, their recipients are the whole of the city’s inhabitants and visitors, and they should be used to the maximum of their potential, not limiting their use to licensed terraces for bars and the hospitality industry.

More cities are increasingly thinking of strategies to attract future residents, rather than tourists. Another one of the big trends emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic was the exodus from the big cities to regional, mid-sized and small urban areas, where the quality of life and the access to nature was better. While a lot of this has reversed, there is an argument to be made about the city-level strategies that focus on attracting residents, rather than visitors. In the under-populated areas of central Spain, for instance, that is a big trend, where culture and access to the arts usually play a big role. Would Homer’s music scene change if it were geared to attracting people to come and stay to live in the city?

Innovation in urbanism and cultural planning is not replicating what bigger cities are doing, but adapting that to the needs of the local cities. One of the best ways to start doing this is through participatory processes that include “unusual suspects” – people and stakeholders that would not normally take part in these conversations.

TIPS AND REFERENCES

Of two different cities, of different sizes and different levels of cultural offer, working from a network approach: Porto and Braga, in Portugal. Braga is a medium-sized city that is close enough to Porto to have access to their infrastructure and offer, yet it is self-sufficient in terms of cultural activities and offer for visitors.

Of a remote place that is promoting itself through leaving space for local identity: Rovaniemi, in Finland, putting Saami culture at the centre of their visitor offer.

Of port cities attempting to plan programming around the cruise times that targets both visitors and locals: Piraeus, in Greece.

CASE STUDY 3

Synergies between cultural policies and climate change

Chiara Badiali and Sam Lee receiving a WOMEX19 award on behalf of Julie’s Bicycle in 2019. Image by Yannis Psathas

Julie’s Bicycle (London, United Kingdom)

Julie’s Bicycle is a non-profit organisation based in the UK focused on mobilising the arts and culture to take action on the climate, nature and justice crisis. Founded by the music industry in 2007 and now working across the arts and culture, it has partnered with over 2000 organisations in the UK and internationally. JB combines cultural and environmental expertise to develop high-impact programmes and policy change to tackle the climate crisis. Julie’s Bicycle focuses on high-impact programmes and policy change to meet the crisis head-on.

Their first of its kind Future Festival Tools, learning resources for professionals to embed sustainability within their careers, prove to hold an enormous potential for impact in mainstreaming environmental action throughout all events and job roles.

Their projects range from sustainability consultancy, to advocacy to developing environmental and impact measuring tools. They also maintain and regularly update a Resources page, where they link case-studies, guides and research on the topic of climate-sensitive cultural policies, for example this Climate Risk Mapping of London’s cultural venues by Bloomberg Associates.

Key learnings and important points of connection for Homer:

De-growth is the way to go. For festivals and events, the question of whether to go smaller or not is slowly less of a question and more of a need – only through controlled numbers are festivals and event operators able to keep the amounts manageable and the ecosystem local, something that surfaces in several examples worldwide. Furthermore, smaller events are also more likely to have sustainability in their philosophy.

Prioritise the local ecosystem. Festivals and showcase events are key meeting points for the industry, yet the impact of flying and other unsustainable practices related to travelling are important to take into account. Rethinking timings (gatherings going from annual to bi-annual) and the target audiences (international vs national and local) can be good entry points.

Use music gatherings as spaces for experimentation. Few large-scale challenges are as immobilising as climate change for some audiences, especially in light of a very usual feeling of over-complexity and helplessness. Music events can also position themselves as spaces for experimentation and reflection on these topics, becoming catalysts for social and ecological organising.

Beware of greenwashing. A good communication strategy simply won’t do – actions need to back the words, otherwise sooner or later both audiences and governments (those who care) will notice if promises are empty.

Other societal problems might be considered more urgent and have priority. In these instances, using culture to center climate issues is key.

Training is important. According to The Shift Project, Decarbonize Culture! Report 2021, 88% of cultural professionals in France are not trained in energy and climate issues. Those numbers may vary geographically, yet they speak to a blank spot that is crucial to create change.

Test the technology. Interesting and exciting tools are being explored worldwide – a quick scan can shed light on possible ideas whose implementation might be just fit for your local context.

Use music to restore the ecological value of places. Either by bringing awareness or by relocating activities, music events and cultural practices can be powerful actors of territorial management and land planning.

Organise collectively. Changing the status quo is never easy – and these large-scale fights will always be more successful when there are more and more people involved. Find partners and strengthen the networks.

Sustainability is not only environmental – it is also economic and social, and when it is not addressed holistically, supporters might be lost along the way.

Other relevant examples, organisations and research on this topic:

Reset! Network’s Atlas of Independent Culture and Media, Volume 2 (EU)

Volume two of this landmark work by the European network Reset! – a sensitive cartography of independent realities in Europe – is entirely dedicated to the cultural sector’s pursuit of ecological commitment, featuring interviews with organisations, people and change-makers that have the environmental transition at the core of their cultural work.

The Shift Project (FR)

The Shift Project is a French think tank advocating the shift to a post-carbon economy. As a non-profit organisation committed to serving the general interest through scientific objectivity, we are dedicated to informing and influencing the debate on energy transition in Europe. In 2021 they published a report called Décarbonons la Culture! (Let’s decarbonise culture!) focused on the French context. This was the fifth publication from a larger Plan of transformation of the French economy. From their report, there are a few key directions for festivals and events that are good advice on this topic:

Relocate activities. Place culture at the heart of territories and make it a driving force for local transition.

Slow down. Artists will continue to travel… Stay extended / reduce the number of trips.

Reduce the scales. Rethink the permanent growth of audience size.

Eco-design. Take into account the global impact of a scenic or scenographic creation (life cycle analysis).

Renounce. To certain high-carbon practices already in use and high-carbon technological opportunities.

The Nile Project (US)

International nonprofit that promotes the sustainability of the Nile River by curating innovative collaborations among musicians, university students, and professionals. It later evolved into a concert performance that toured around the world. Founded by Egyptian Ethnomusicologist Mina Girgis and Ethiopian-American singer Melkit Hadero.

Arts & Climate Initiative (US)

New York-based organisation using storytelling and live performance to foster dialogue about the global climate crisis. Primarily focused on theatre and performing arts. Initiators of the Arts and Climate Change blog, which aims to compile all works of arts about climate change.

Art Switch (US/NL) New York and Amsterdam-based nonprofit in the field of Art and Climate Action founded in 2019. Focused on education, engagement and fostering connections between artists, scientists, academics, and art professionals. Multidisciplinary platform centering on public programming, conferences, and exhibitions with a focus on climate forward and regenerative art practices.

The Green Room (FR) Sustainability consultancy based in France working to support environmental and social change in the music sector. They develop strategies, set up low carbon tours, carry out evaluations, create programmes for raising awareness, deliver training. They are also regularly invited to music conventions and network meetings in France and abroad.

Ki Culture (NL) Ki Culture is an international nonprofit working to unite culture and sustainability. Their focus is on culture in the widest sense, as well as sustainability in economic, environmental and social terms. Their focus is on training and knowledge‑sharing.

ClimateMusic (US) San Francisco-based organisation focused on combining the talents and expertise of scientists, composers, musicians, artists, and technologists, to create and stage science-guided music and visual experiences to inspire people to engage actively on the issue of climate change.

Greener Events (NO) Greener Events is a practical oriented, non-profit organization which assists sporting and cultural events in forming strategies and acting sustainably. They deliver environmental consultation, expertise in planning and running events, consultation in certifications and CO2 reports as well as creating tools to help the sector achieve its sustainability goals.

Reverb (US) Portland-based nonprofit dedicated to creating a more sustainable music industry. They partner with musicians, festivals and venues to green their concert events while engaging fans face-to-face at shows to take action on important environmental, climate, and social issues.

Music Declares Emergency (UK) UK-registered charity founded by a group of artists, music industry professionals and organisations dedicated to raising awareness and creating action around climate change in the music industry. Through campaigns like NO MUSIC ON A DEAD PLANET they focus on shifting communication dynamics around climate within the industry and advocating for an environmentally-friendly sector.

Clubtopia (DE) A Berlin-based organisation devoted to sustainability and climate matters within the city’s club scene, addressing clubs, event organisers and guests with the goal to raise awareness and change behaviour in the industry. Their Green Club Guide was recently made available in English.

PART 5

Conclusion and Final Recommendations

Key learnings for the local partner and most pressing next steps

A recurring theme in roundtables and case studies is the need for additional data on stakeholders in the music ecosystem as well as collaborators. A specific demographic within the ecosystem is particularly important to map, understand and involve: youth. Recruiting youth as players as well as audience members is a prevailing sustainability challenge for arts and presenting organizations. Explorations are needed which may yield concrete plans for youth leadership development in the music sector, including improved All Ages access to performance opportunities and venues.

Venues and space are another key issue in Homer’s music ecosystem. Over several decades, local studies and public surveys have established that there is a lack of performance spaces. This document includes within that observation rehearsal spaces and youth-activated music spaces. While there remains potential for small venues and events, most avenues have been explored – local organizations, for example, have long looked into repurposing facilities and developing creative partnerships for pop-ups. New businesses may arise as feasible collaborators, but a multi-organization community partnership would be necessary to create an actual new venue.

With regards to the case-studies analysed during this project, there are two main learnings.

Firstly, although public subsidies such as those in Tórshavn are not realistic in many small cities in the United States, close connection and communication with the City of Homer government (particularly technical staff) will help to align the music ecosystem with City planning and policy.

Secondly, while Homer cannot claim a 24-hour economy, innovative and further use of public spaces and the promotion of music and arts to attract long-term residents are key takeaways from the Cities After Dark case-study.

Scott Bartlett,

Musician, Producer, Executive Director of Homer Council on the Arts

Yngvil Vatn Guttu,

Composer, Musician, Educator and Founder and CEO of Northern Culture Exchange

Overview of key recommendations for next steps

Short term (0-12 months)

1. Connect, establish and strengthen relationships with the City of Homer

a. Reconnect with representative(s) of city council present during roundtable, as well as other assembly members or Mayor’s office staff.

b. Establish regular communication with key technical staff.

c. Share key facts, activities, initiatives and case-studies from the music ecosystem with them.

d. Suggest intention-based partnership to explore key policy commitments (see further below, in long term).

2. Recognise Homer as a Music City, ensuring commitment from the municipal Assembly

a. Explore the establishment of a Music Office (implementation can be longer term), unpacking the steps that would be necessary and the financial constraints attached.

3. Explore and establish partnerships with other key organisations, such as Homer Chamber, Visitor’s Bureau, NGOs and Foundations.

4. Increase collaboration across sectors and with the community

Break down silos and create stronger communities through deliberate and intentional engagement with music and local musicians.

a. Coordinate with community centres.

b. Explore ways to integrate visiting musicians with local advocacy and awareness work.

Medium term (1-3 years)

5. Support youth and accelerate education through music

a. Map and examine the status of current in- and out-of- school music education.

b. Think of and propose key innovations within music education (e.g. rotating visiting artists in classrooms), in particular applying a broad understanding of the concept of ‘music-making’, in order to encompass learning on culture, identity, emotional education, etc.

c. Develop youth leadership capacity building workshops with local champions and role-models. Ensure representation and access across all demographics.

6. Advocate for and create an all ages venue in Homer

This can be in the form of: An all ages event series in one or several already-existing venues in Homer: pop-up events or “takeovers” at existing places; or developing a new governance and programming model for one existing venue that can become an All Ages venue; or for a newly created space. For the execution of any of these, take into account:

a. Do not reinvent the wheel: find key references of all ages venues in the U.S. or internationally, set up learning calls with them and create a governance plan based on their learnings.

b. Ensure transparency and clear governance standards for the venue or event series.

c. Develop and implement a participation strategy, also for programming. d. Ensure equity and representation across all activities within the space or event series.

7. Develop and implement a transparent and diversified funding strategy

a. Explore ways to attract and utilise private funding from philanthropy, foundations, trusts and other potential donors from national and international funders.

b. Explore blended funds and efficient ways to integrate public and private funding for music.

c. Connect with representatives of other key sectors related to music such as tourism or health, align priorities of the music sector with these, and explore collective fundraising.

Long term (3-5+ years)

8. Map the music ecosystem of Homer

a. Conduct a comprehensive, data-driven mapping exercise that quantifies all actors in the ecosystem, from venues, to audiences, to youth organisations.

b. Develop a system for detailing the impact of mapping music infrastructure, places and spaces.

c. Publish a Music Map, either separate form or ideally incorporated within the existing Art Map.

d. Publish a Music Business registry (AK Music Census).

9. Develop a comprehensive, long-term cultural vision and policy, featuring a dedicated music section

a. Process findings from mapping exercise and develop a comprehensive participation strategy featuring consultation sessions with key actors in the music ecosystem.

b. Develop and execute a qualitative research exercise to unpack pains, needs and challenges of the different actors in the ecosystem.

c. Initiate, sustain and nurture relationships across other art fields, aligning demands and needs.

d. Develop a dedicated music section within the policy, featuring, among others: i. Busking rules,

ii. Funding rules (Mayoral / Homer Foundation Music grant),

iii. A Music Summit event in collaboration with Music Alaska,

iv. Orientation on statewide Brewery and Meadery music regulations.

e. Develop, propose and ensure monitoring mechanisms to ensure compliance and yearly revision of implementation of the policy.